A bit about The Underfoot

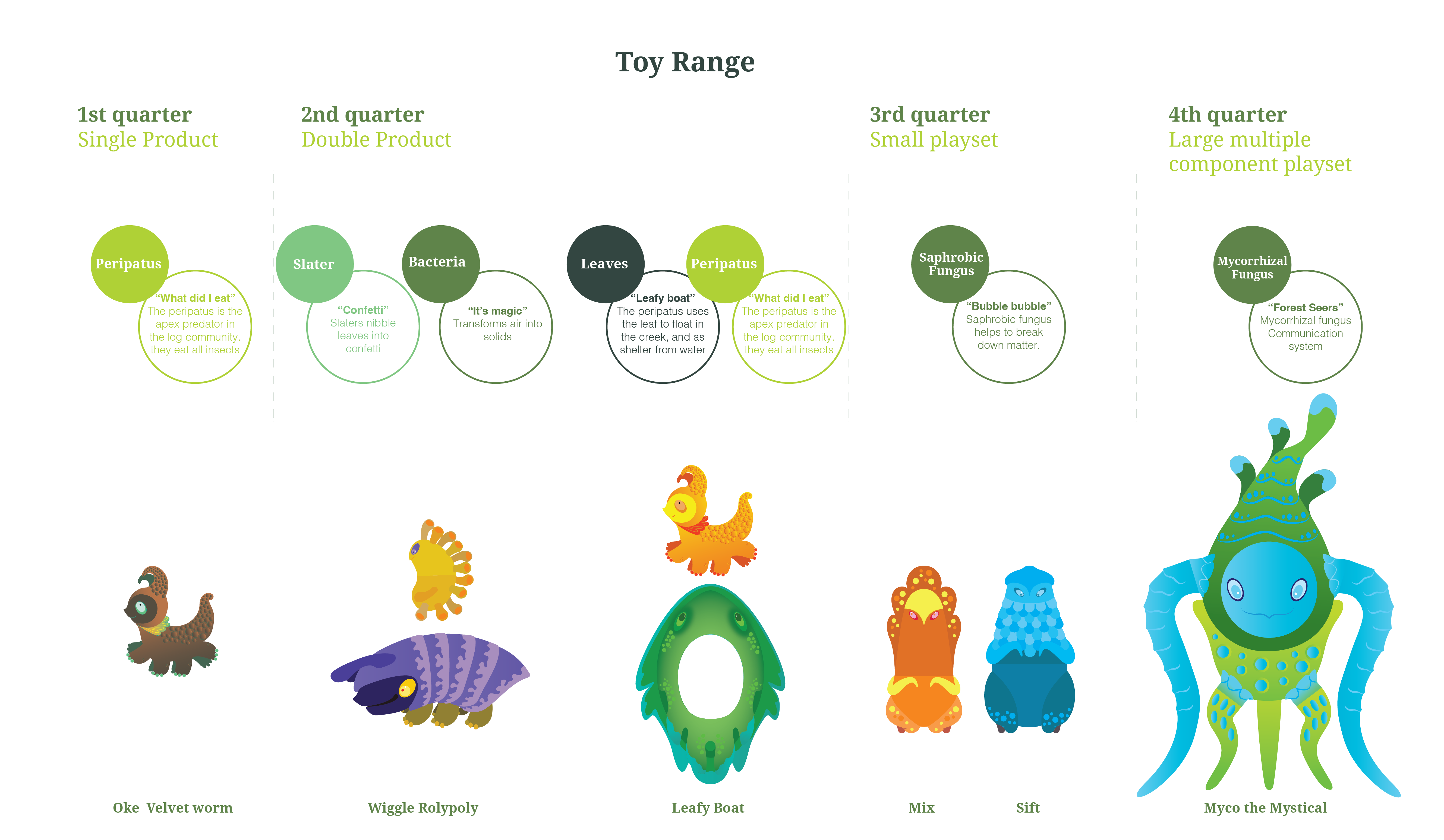

This creative doctoral research project aims to design a series of character toys, which both embody an eco-fiction narrative, but also are themselves an ecosystem. The resulting works seek to encourage New Zealand children aged 5-7 to engage with environmental narratives while playing with the design objects. The research is due for completion at the end of 2023.

Children engage in less outdoor play than previous generations. This global trend has impacted on a child’s ability to understand and form a relationship with the natural world. Described as ‘nature deficit’ disorder, the decline in nature play can affect a child’s ability to self-actualise and develop relationships with non-human living beings. This practice-led creative research used eco-fiction design criteria to develop the Underfoot range of five-character toys and a pitch document that encourages Aotearoa New Zealand children aged between five and seven years old to engage with environmental narratives while playing with the toys in nature.

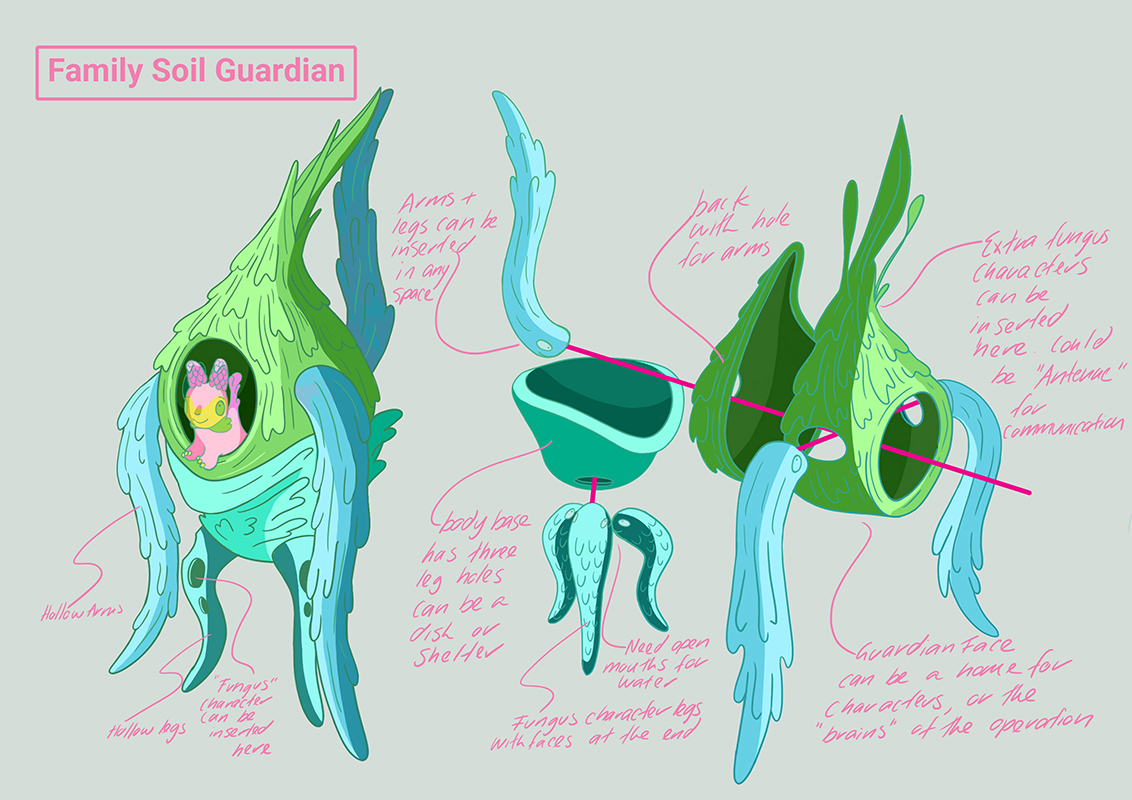

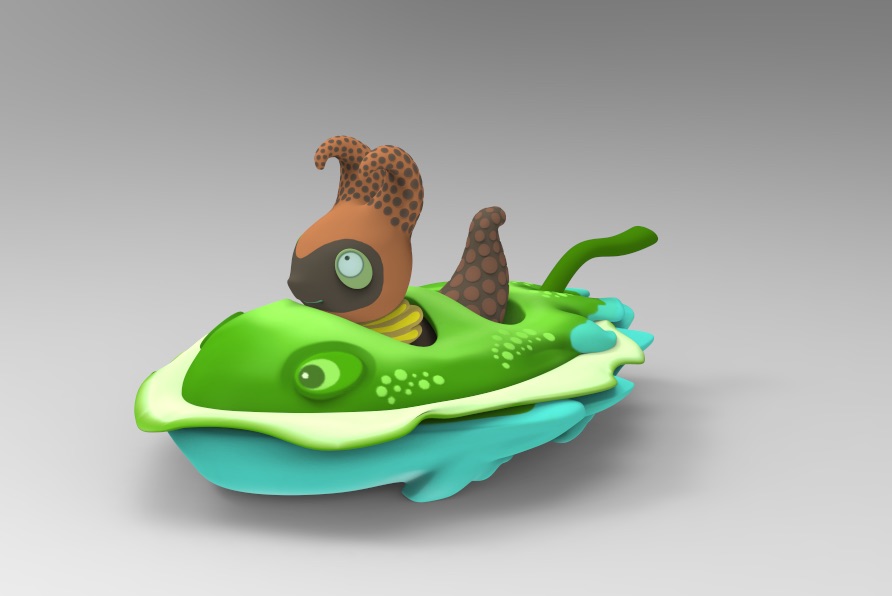

The Underfoot character toys are themed around the nitrogen cycle system and focuses on character play in outdoor spaces. A core design feature is the integration of natural materials such as soil, leaves and water during play as part of the toy’s character. The pitch document describes the toys story world, the character’s motivations and their ecosystem. The Underfoot toys demonstrate how eco-fiction character toys can enhance a child’s relationship with the natural world through appraisal by industry experts and playtesting with child user groups.

A bit about Wildplay

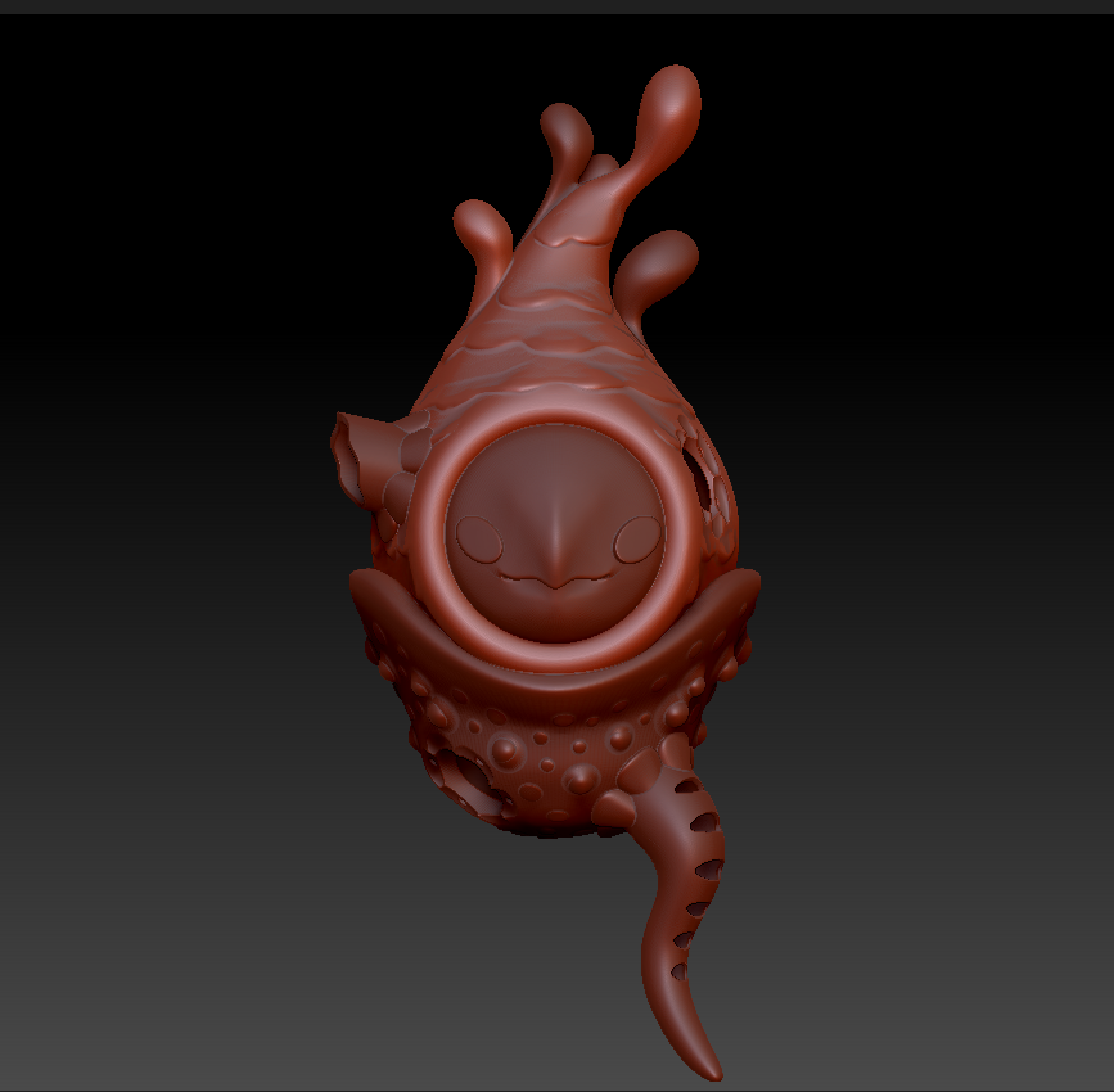

Figure 1: Myco the Magnificent Underfoot toy. Design by Tanya Marriott

The Research

This research developed a range of eco-fiction character licence toys – The Underfoot for outdoor play that encouraged children aged 5-7 to engage in ecological principles during play. The research questioned the current design process for developing character toys. Using an eco-fiction framework during the design process enabled the design of more ecologically embodied toys. As a doll and toy designer for many years, personal observations highlight that well-designed toys can be powerful pervasive agents for environmental awareness as well as interconnectedness with the natural environment. This research suggested that such toys can instil a deep ecological understanding and relationship with natural spaces and other species in the next generation.

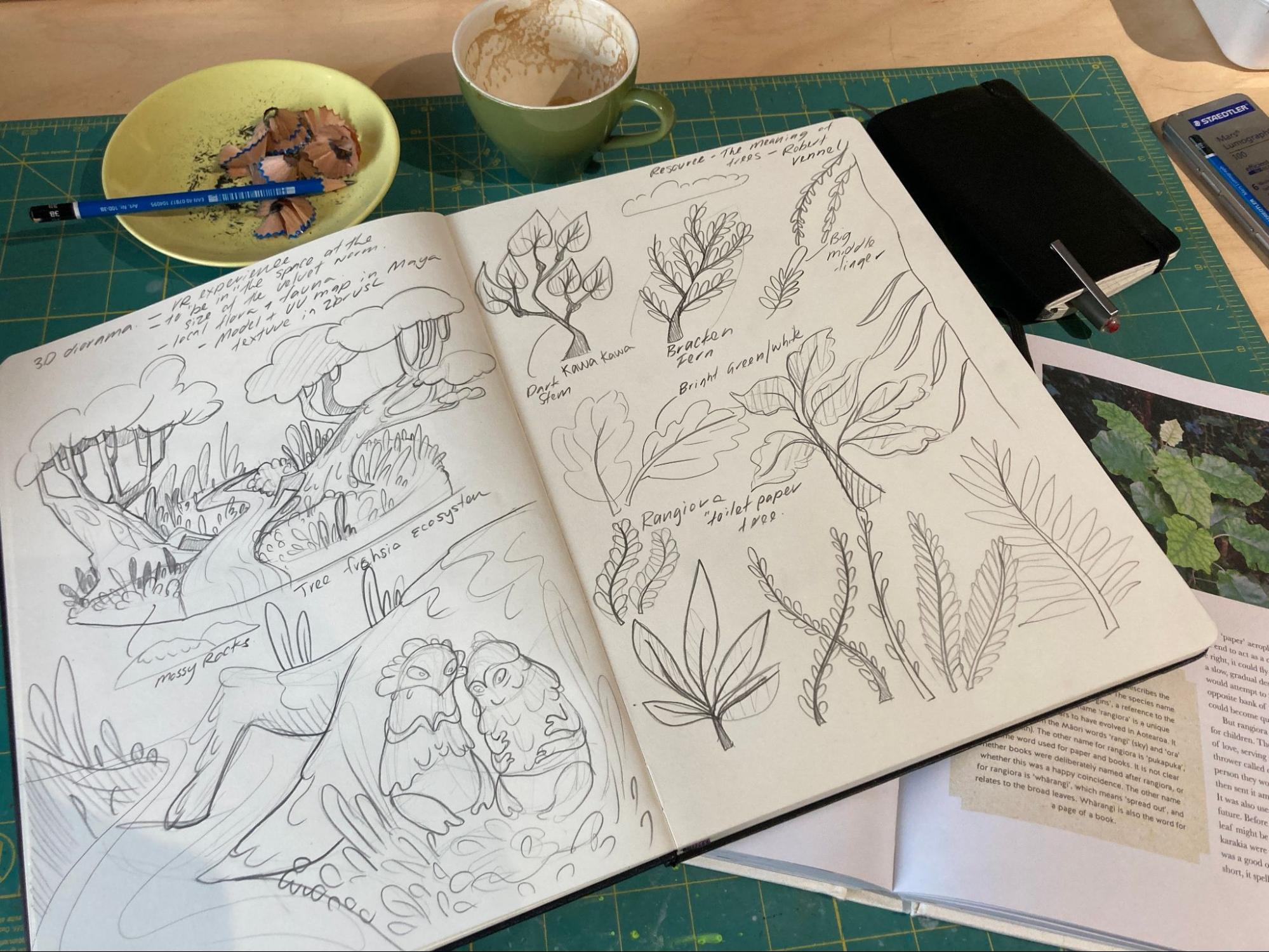

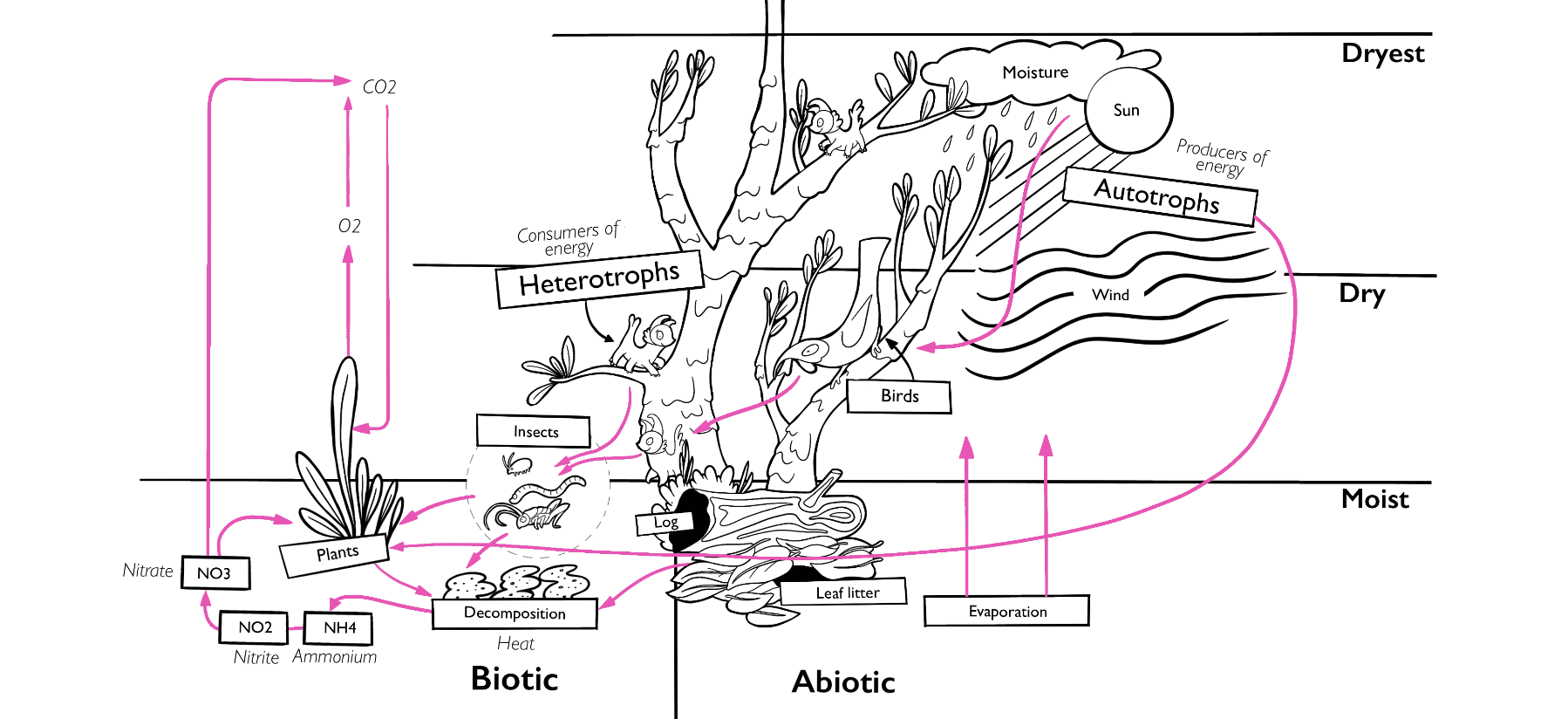

Character toys (defined as dolls and action figures) are not designed for outdoor play, which this research views as a missed opportunity to use character toys as agents to empower nature play. The research defines and documents a cyclic design methodology that enables the toy designer to action a cohesive environmental narrative from media licence as a pitch bible into the Underfoot character toy range. The eco-fiction narrative framework guides the design process for the character toys, which are designed as an ecosystem of interlinked products that utilise natural materials and environments as an extension of the play product. Real biotic and abiotic species within living soil ecosystems influence the design of the toy characters, with the Velvet worm, a “missing link” creature from Aotearoa, New Zealand, used as a key character due to its ecological uniqueness and potential for characterisation.

Children aged five to seven play tested the toy prototypes over several sessions in a public wilderness park. Observations indicated high levels of environmental immersion through play with the toys. The young respondents used the toys to explore the natural environment and interact with other species and plants. Findings indicate that the toys encouraged the children to engage in nature and form connections within the natural world. The method of design, which used an eco-fiction framework to enable the cohesive integration of environmental narrative between the media licence and the toys themselves, enabled the research to embody ecological principles and systems within all aspects of the design. The Underfoot toys were exhibited at the Nuremberg Toy Fair in 2023 and reviewed by toy industry experts.

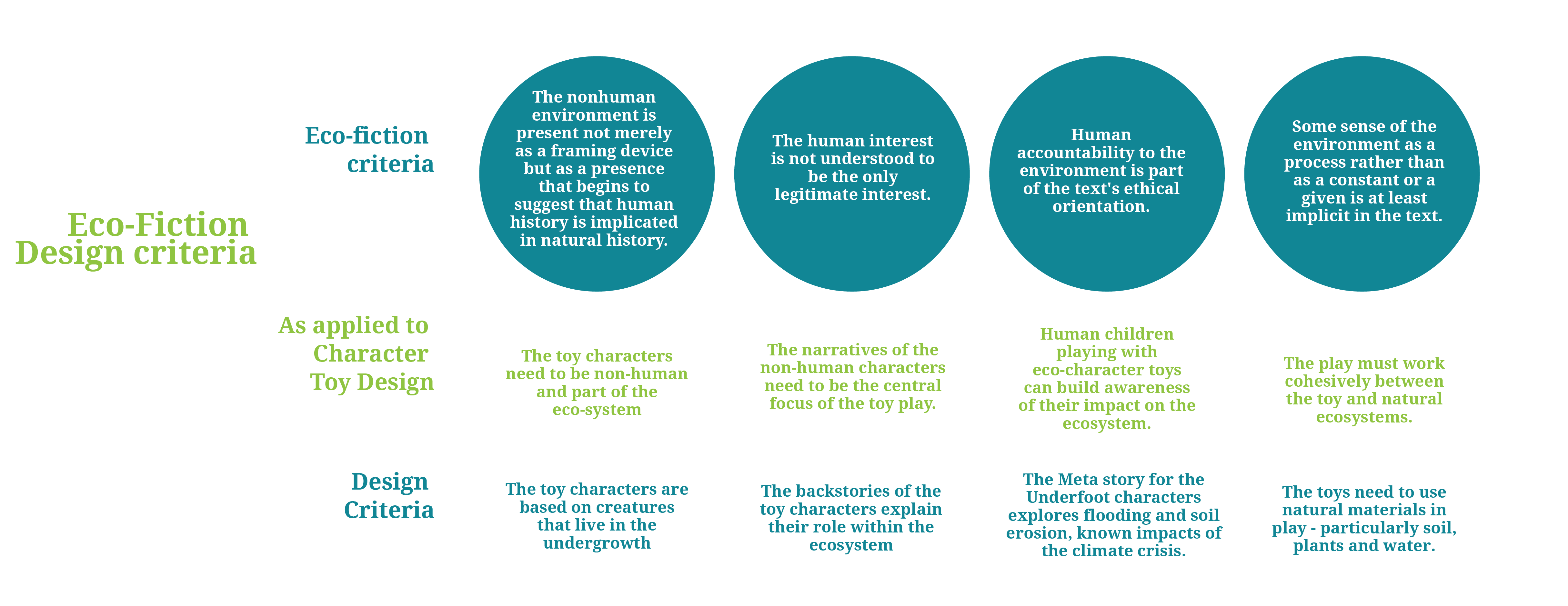

Figure 2: Eco-fiction toy design criteria.

The ecology of Imagination

Well-designed toys used within play are the agents for whatever the child wishes to explore, enabling them to form an understanding of the world around them through active exploration, mimicry and imagination. Brian Sutton-Smith (1986) describes toys as signifiers that enable children to play with them as universal objects, not simply as they have been defined. A doll can be a proxy for whatever fantastical character a child can imagine. Edith Cobb (1977) states that “child’s play enables them to be something other than what they actually are and to dramatise speculation” (p.29). Imaginative play is the form in which children build an ability to creatively problem solve and make meaning of the world. The ecology of the imagination is the formation of interconnected relationships between children and everything around them.

Decline in Play

There is a decline in childhood outdoor play, with contemporary children are better able to identify Pokemon characters, than local flora and fauna (Robinson, Inger, Gaston, 2016). Richard Louv (2005) founder of the Child in Nature network, indicates that the lack of outdoor play is likely to have drastic effects on a child’s ability to imaginatively and creatively play, and their greater emotional well-being. Children are spending more time invested in online content – games, TV, animation or in structured activities. Toy play outside enables children to form an intimacy with living creatures, and elements of the natural world that do not exist in a sanitised inside world. Through this interaction, they learn to appreciate dirt and mud, wind and dampness, and how these environmental factors affect the creatures that live within the space.

Eco-Fiction narratives

Eco-fiction narratives are stories that centre on an environmental theme, where humans are not the central focus of the narrative, but rather a component within a wider ecosystem (2010). The term eco-fiction refers to literary texts, animation and film. Eco-fiction narratives were particularly prevalent within early licensed toys with a strong emphasis on human creature hybrids and an interconnected and magical relationship between character and environment. The four part eco-fiction criteria privileges the narratives of the nonhuman ‘other’ as legitimate histories, and not just a framing device for human interests, and that the environment is an evolving process, not a static entity.

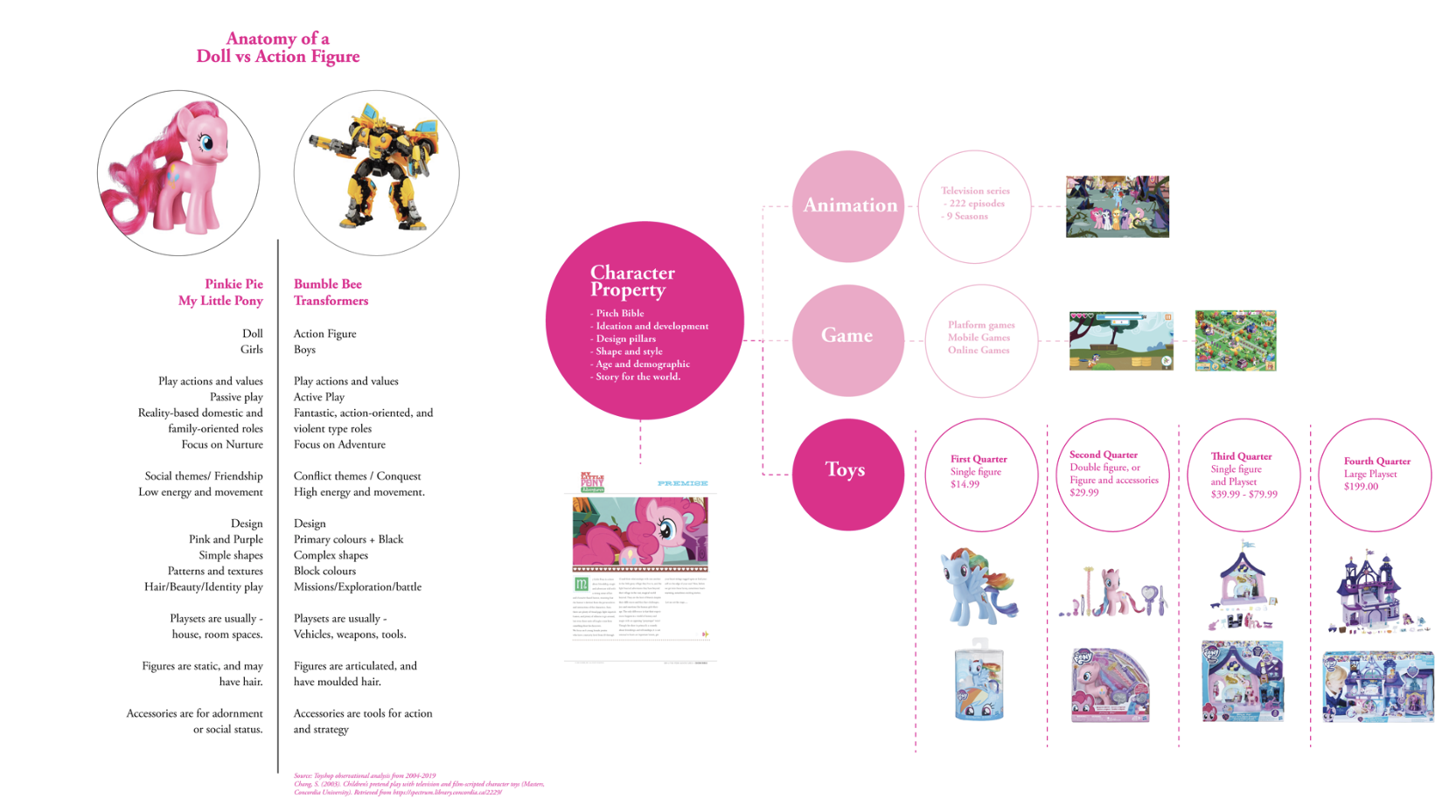

Character licence toys

Dolls and Action figures are still popular toys, especially when driven by entertainment properties. Since the 1980’s Toy companies have used these narratives to frame the world behind the toy and to trigger the starting point for imaginative play to occur. The toy association defines this toy genre as doll and action figure-based toys derived from or aligned to an accompanying animation or game media licence. The story worlds children create for their imaginative toy play are motivated by both the child’s reality and the toy stories within consumed media. In previous generations, children took their character toys outside to play. Through their activities, they discovered and built hybrid imaginative play worlds that, significantly, were inhabited by a combination of commercial toys and natural objects. However, dolls and action figures are not evident in the toy industry’s descriptors of outdoor toys and are not designed for this mode of play.

Character Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is an epistemology that enables emotional relationships to be formed with objects to give them meaning (Clayton, Clayton, & Opotow, 2003). It is a common form of humanist characterisation within toy design as it enables children to emotionally invest in the toy and within the toys own world. Children similarly anthropomorphise animals and plants. However, they are less likely to anthropomorphise more significant concepts such as an ecosystem. This could be due to how ecological systems are presented within children’s media. Human characteristics are given to “animals, plants and trees, but not to an ecosystem as a “whole”. This research suggests that toy intangibility through play actions gives them a form of life force or spirit. This research indicates that referencing environmental narratives within toys at the core level of play and storytelling is fundamental for children to reconnect to an understanding of ecology.

The Peripatus

The Peripatus has been chosen as the case study character. It is crucial to centre this research on a specific creature, so that a focal point for story, characters and the wider ecosystem designs to be defined. Peripatus, Velvet worms, or Ngāokeoke, Are also referred to as the “missing link” (Gleeson, 1996). Peripatus have the characteristics of both worms and insects, being Long and wormlike with multiple sets of legs and flexible bodies. They are brightly coloured and patterned, nocturnal, and live in matriarchal family groups. They are both predator and prey and are highly territorial and protective of their immediate family.

Figure 3: Character licence toy breakdown. Diagram by Tanya Marriott

Figure 4: My little Pony G1 Cascade and waterfall playset. Photo taken by Tanya Marriott

Figure 5: Existing animal toy review. Diagram by Tanya Marriott

Figure 6: Euperipatoides rowelli, a velvet worm (Peripatopsidae:Onychophora) Image taken by Andras Keszei (Keszei, 2011).

The Design

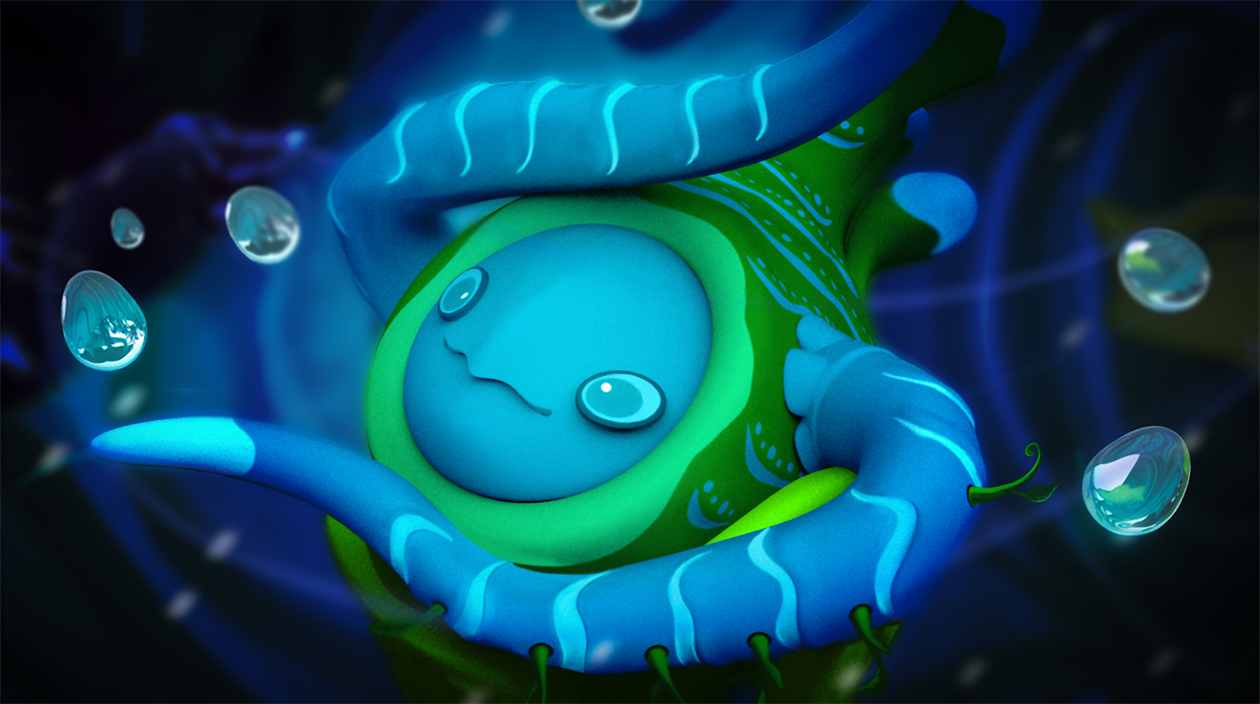

Introducing the Underfoot

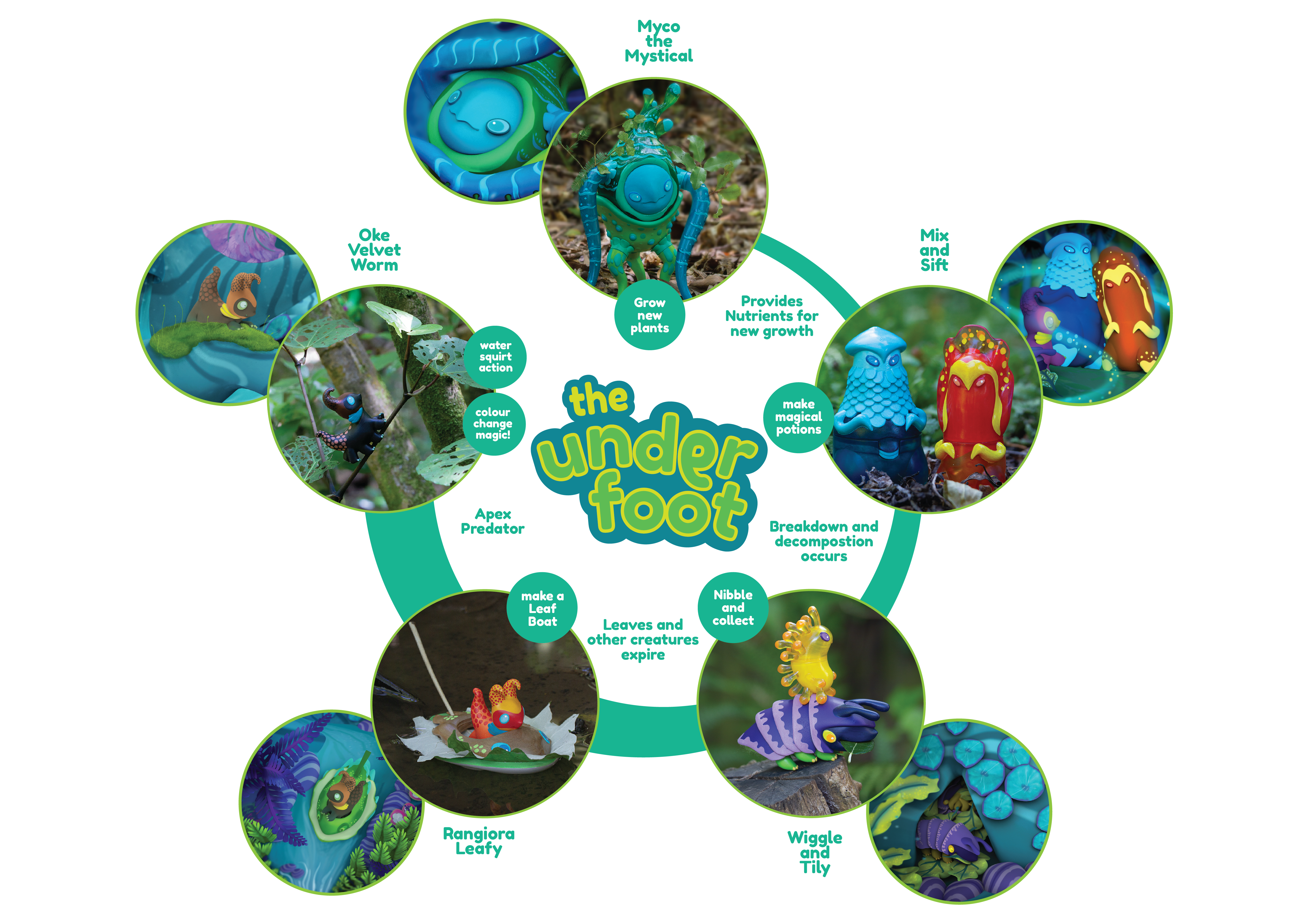

The Underfoot character toys are designed to be played with outside in the dirt and undergrowth within the garden. Together they make an ecosystem of toys, each influencing the others in a larger cycle of narrative play. Play with the Underfoot toys outside enables children to engage in the magical natural world. The Underfoot range is designed for children aged 5-7, a key age when children develop their imagination, communication and social skills and interact more independently with the natural world.

Eco-fiction characters

For the toy characters to be part of an ecosystem, site surveys and ecological research into soil creatures and systems were conduced. An ecosystem comprises a diverse array of species that enable the cyclic systems to function, so for the underfoot range, I used the Nitrogen cycle of decomposition to define the toy ecosystem and chose a selection of creatures, both biotic and abiotic, to act as agents of play. The species I chose to define the characters needed to be ecosystem inhabitants. Additionally, they needed to have interesting habits, aesthetic features or ecological functions that made them potential toy characters. I used the Trophic levels to define the hierarchy of character toys, with the Peripatus (velvet worm) chosen as the central character due to its duality as a cute and appealing apex predator.

Figure 7: The Underfoot! design brief matrix. Diagram by Tanya Marriott

Eco-fiction narratives

The story world is embodied in the character toys, packaging, story snippet and character artwork. “At the bottom of the garden, the home tree stands on the stream’s banks. This is the magical home of the Underfoot, guardians of the forest floor. They help to keep everything in balance” To develop a Meta narrative for the Underfoot characters, I looked to Concept design principles of world-building to establish three core pillars for the world

- The characters live in a home tree

- The character relationships can have tension and challenge

- The ecosystem is affected by flooding.

These three criteria are based on a need to ground the world in some form of believable reality. The creatures in this ecosystem are tiny, so they all live in a similar location. Having a home tree builds on the notion of the tree house but frames it with ecological principles in mind. It makes it easier for children to engage in small-world play as they can centre their play around the roots of a tree or a shrub.

Eco-fiction system

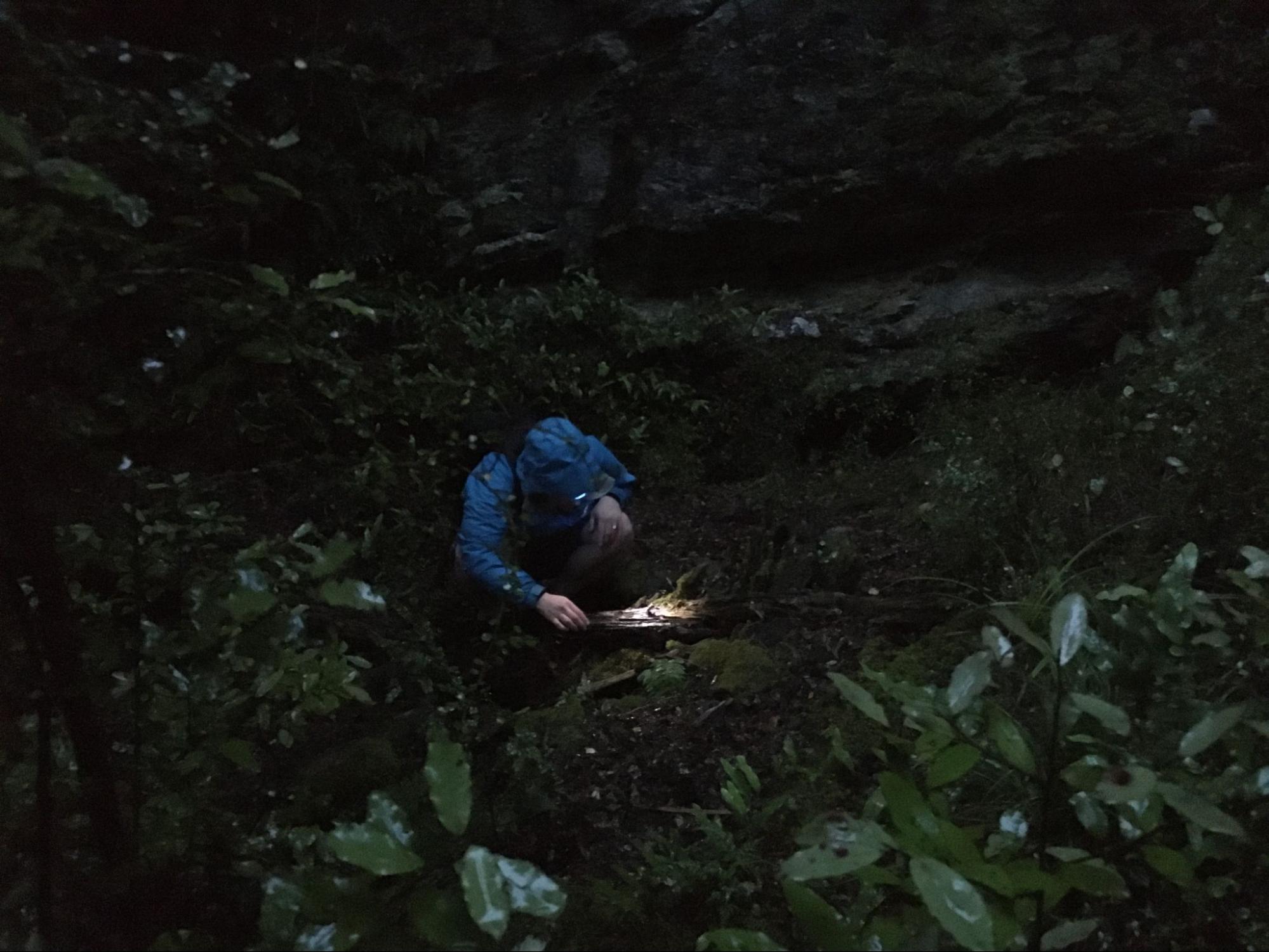

I prototyped and tested the toys outside to ensure the design was enhanced by integration into the natural world and how the design of the ecosystem could become the wider playset for play. During playtesting, there were several instances when children slowed and commented on ephemeral natural transitions that, had they not been intimately engaged in a natural space may not have noticed.

Core to the design is the Underfoot toy as an ecosystem to enable an interplay between the toy itself and the natural world. Play is a transformative process, so the toys use natural materials to make the play distinctive. During playtesting, most children defined Mix and Sift as Potion makers, but the type of potion making changed by the child and by locale materials. By encouraging play in the dirt and leaf litter, the matter was also transformed as it was moved from between toys – A leaf started as shelter and a boat, but as it breaks down, it becomes food for another character toy.

Playtesting

Playtesting Grey and Colour models

Two playtesting sessions with children aged 5-7 were conducted at a public wilderness park, the site selected as it was easily accessible. The focus group involved 9 children across both sessions. Both playtesting sessions lasted 45 minutes. I analysed six hours of footage and conducted follow-up interviews with parents about continued play. For the first playtesting session, children were introduced to the toys at 10-15 minute intervals. They were shown digital illustrations of the characters in the story world and given an overview of the character narrative. The grey models were used to test for story coherence, character engagement and product function. This session was used to observe how children wanted to use the toys.

In the colour playtesting session, children played with the final designs. All children engaged with the toys. Two children engaged in narrative character play and used the toys to develop independent stories. Two other children used the toys in construction play and used the toys to make ponds and water containment. One child became the character through play and was immersed in the natural space. Once children found a toy they preferred, they remained in play for 45 minutes and only stopped when called back by the researcher. The children used natural materials with the toys – predominantly dirt ( mud), water and leaves – both off the trees and on the ground. Most children read and used pamphlets with toys to understand them. Several children were content to be in the forest, whereas others got into the flow during independent play. Although most children did not play the prescribed narratives of the toy characters, they did use the toys to engage in nature play, which could not be achieved indoors. They observed some ecological phenomena during play – the creek was deeper than last time, the fungus were children, they fed water to the trees, and observed spiders and other creatures in a manner that indicated some ecological awareness and respect.

Figure 8: Playtesting with the colour prototypes. Diagram by Tanya Marriott.

Figure 9: Playtesting with colour models. Diagram by Tanya Marriott.

Findings

Appraisal

The toys were previewed at the 2023 Nuremberg toy fair to positive feedback and appraised by three veteran toy industry designers. The underfoot’s colourful characters and bold shape language contrasted sharply with the neutral tones of other nature-focused toys. They garnered positive feedback for the product, with comments on the freshness and uniqueness of the range. There was an overall appreciation that the characters were a system combined with Nature as the playset, as the play was ever-changing. The depth of the story world opened up possibilities for further products. There were concerns regarding the level of anthropomorphism of the toys; could they be too far from humans for children to relate to. The appraisal from toy designers had a range of thoughts, with colour giving conflicting opinions. The bright colours would appeal to children and enhance fantasy play, and that colour would make it easier to find missing parts. Another designer was concerned that they felt too much like designer toys and would be too precious for play. There was a general assumption that Nature is green, despite the vibrancy of the natural world at a micro level. The toy designers felt that even if the children don’t understand the principles of symbiotic relationships, the toys enable them to be explorers in their own way with fun and colourful creatures. The need for children to go outside to use natural objects to complete the play was of great appeal and a pivotal selling point of the product.

Findings

This research was overall successful in engaging children in outdoor nature play. Using eco-fiction design criteria helped the designer step away from an anthropomorphic design mode and develop a range of characters for a more sensitive ecosystem worldview. The children found the characters’ anthropomorphic Nature appealing and could use the visual and narrative cues from the toys to inform imaginative nature-influenced play. The playtesting sessions demonstrate a sustained interest in small worlds play with the toys and an ability for the toys to enable children to slow down and spend more immersive time playing in Nature. The findings show several areas for further development. The character toys, as a design, demonstrate an ecosystem, both in the narrative and implied play cycles. However, this was not picked up by the children, who still saw them as independent characters rather than a system. The playtesting samples were small due to the bespoke Nature of the prototypes, so testing with a larger group, where children have a longer experience with the toys, would yield more conclusive data. The appraisal from the toy industry showed an interest in the design of character toys for outdoor play. However, it felt it would still be challenging to sell this idea to parents and how the product would be promoted alongside similar character-licenced toys.

Figure 10: Mix and Sift in the forest. Prototype by Tanya Marriott.

Figure 11: Luna Velvet worm and Wriggle Rolypoly. Prototype by Tanya Marriott.

Final Designs

Further information

If you are interested to know more about this project, please get in contact – t.marriott@massey.ac.nz